Current Temperature

-3.9°C

Anti-imperialist thrust in Orwell’s Burmese Days

Posted on September 26, 2019 by Vauxhall Advance

By Trevor Busch

Vauxhall Advance

tbusch@tabertimes.com

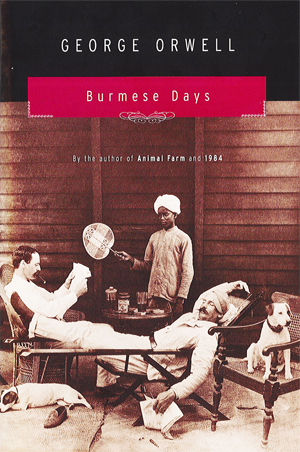

When most people think about George Orwell, it is usually the anti-totalitarian buzz words that come to mind — Thought Police, Big Brother — and the popular success of his immensely influential political novels that came very late in his life and career, Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949).

Little more can be said that hasn’t been already about these latter works of Orwell’s fiction, one a dark allegorical novella read by generations of school children, the other a dystopian masterpiece virtually unrivaled in this sub-genre of fiction, and probably Orwell’s finest. The controversial author died from tuberculosis complications in January 1950 shortly after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four. It has always been a matter of lamentable speculation for fans of Orwell’s work just what he might have put to paper later in his career had he lived longer than his 46 years.

But long before he published his hallmark works, Eric Arthur Blair (George Orwell is actually a pseudonym) penned a number of novels that display many shades of the social and political commentary for which he would later become justly famous. One of these early novels is Orwell’s anti-imperialist polemic, Burmese Days (1934). A harsh indictment of the waning days of British imperial rule in Burma during the 1920s, Orwell drew on his own experiences as an officer in the Indian Imperial Police in Burma from 1922-1927 in setting the scene.

Burmese Days follows a cast of thoroughly unsympathetic characters, mostly made up of European overlords in a stagnant backcountry outpost deep in the Burmese jungle. Nominally a love story of a sort, even Orwell’s main characters like teak merchant James Flory and the vapid young Englishwoman, Elizabeth, upon whom he has set his sights, have irritatingly unpleasant qualities and are both deeply flawed individuals. Which is not to say the novel isn’t worth reading, or completely uninteresting — far from it. But true to form for Orwell’s fiction, those who might be expecting a wonderful happily-ever-after resolution to the novel should look elsewhere for their reading entertainment.

While it can sometimes be depressing to read novels without a clearly-defined hero set in worlds where one must strive to discern any positive qualities about anyone, Flory is simply a protagonist and not a character with any excess of dignity.

Similarly, his love interest Elizabeth is a pure and virtuous product of the English class system who aspires to and admires everything that is reprehensible about it. Though penniless and far from aristocratic herself, she only seems to respect those who are and the positions they retain. The rest of Orwell’s cast of characters are a veritable rogue’s gallery of the detritus of empire, failed English public school types all collected together at a boorish whistlestop in the Burmese jungle surrounded by their despised subjects.

Surprisingly for a political novelist like Orwell who championed the fundamental rights of humanity in much of his work, Burmese Days — read in the light of today’s fascist cult of political correctness, that is — would be considered an uncompromisingly racist novel. It is interesting that Orwell, despite all of his sympathy for the underprivileged — on full display in his previous work, the Depression-era memoir Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) — should have chosen to portray the subject Burmese in such unglowing terms. Orwell’s Burmese have few positive qualities on display, and are written into character in such a spiteful way that it is almost shocking to read some passages where he heaps a form of racist derision on the natives. If not an imperialist, Orwell proved in Burmese Days that he was still a European who harboured much of the “white man’s burden” from his era.

It is worth noting that Burmese Days was published during the interwar period of the 20th century, in 1934. This was an odd time in British imperial history, when colonial gains at the end of WWI were still being consolidated, and the tragedies and triumphs of WWII were still years away. Though certainly an anti-imperialist novel, it is fascinating to see how Orwell still viewed the British Empire at this point in history. The post-WWII era of de-colonization — highlighted by the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947 — seemed almost an impossibility to a British man from Orwell’s generation. While the novel expresses much criticism of British imperialism, it never seems to dawn on Orwell that British pre-eminence and supremacy throughout the globe — deeply weakened by WWI — would ever come to an end, and in a few short years at that.

Subtle but extremely effective in applying his caustic view of British imperialism to his European cast of characters, Orwell manages to achieve his object of projecting these individuals as the lowest and basest people in the district, but at the same time expected to receive the devotion and subservience of their native subjects.

This upending of values — the myth of the purely motivated and benevolent British imperial man — contrasted against the grasping and avaristic reality of British aspirations in Burma, is really one of the masterstrokes of the novel: In the end, Flory is thwarted in achieving the aim of winning Elizabeth not so much by his own many shortcomings, but by the constrained conventions and hypocritical subterfuge of British imperial life. As Orwell said, Flory is “the lone and lacking individual trapped within a bigger system that is undermining the better side of human nature.”

One of Orwell’s first works which casts a light on his early motivations and the development of his political worldview, Burmese Days is a period portrait of the dark side of the British Raj in Burma, but is also a deeper exploration of corruption and imperial bigotry in a society slowly transitioning away from the colonial ethos but still mired in its callous and exploitative practices.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Log In

Log In