Current Temperature

1.1°C

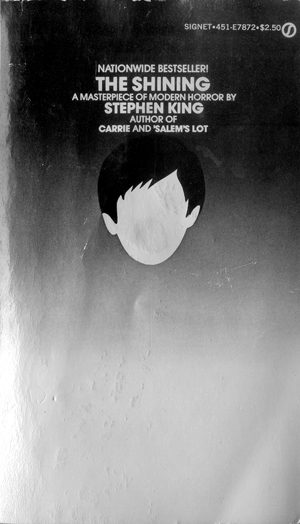

“The Shining” still bright after four decades

Posted on November 29, 2018 by Vauxhall Advance ADVANCE GRAPHIC

ADVANCE GRAPHICBy Trevor Busch

Taber Times

tbusch@tabertimes.com

A cascading elevator of blood. Creepy apparitions of murdered twin girls. An unshaven and maniacal axe-wielding Jack Nicholson bursting through a bathroom door to utter the iconic catch-phase “Here’s Johnny!!”

For anyone that’s been living under a rock for the past 38 years, these are scenes from visionary director Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1980 horror film The Shining. For those of us familiar with the film — perhaps a little too familiar — these scenes have almost grown to the stature of horror cliche. Not unlike Oliver Twist begging for more in Charles Dickens’ 19th century novel, these film elements have become so ingrained in pop culture since the movie’s debut that they are probably easily identifiable to those that have never even watched the opening credits roll.

For authors who sometimes have their source work overshadowed by films based on their novels, one has to express some limited sympathy. Kubrick had the habit of basing many of his classic films on sometimes obscure novels, the most notable example perhaps being Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange (1962) which was adapted for Kubrick’s controversial 1971 film of the same name. The novel had passed without much recognition and only modest sales prior to Kubrick’s film, but exploded in popularity in the early 1970s, probably without the complaint of Burgess on that aspect. However, Burgess later complained bitterly that Kubrick had cut the novel’s final chapter from his film, a chapter where his protagonist appears to be ready to turn over a new leaf with regard to his past crimes.

While author Stephen King’s The Shining (1977) was hardly what one might call an obscure novel, Kubrick’s adaptation would radically alter aspects of the novel’s plot while eliminating others altogether, drawing lasting ire from the New England scribe. Most of us, admittedly, weren’t complaining about the results of Kubrick’s screen vision. But in comparing King’s novel to Kubrick’s unsettling classic, it isn’t difficult to see why the author might have been disappointed.

In many ways — and things rarely work out this way when it comes to film-literature relationships — King’s novel has now been largely overshadowed by Kubrick’s now-classic film, still considered by many to be one of the scariest films ever made and ranked among some the greatest films of the 20th century. With that said, King’s novel is certainly a different kettle of fish, and while a reading of it definitely helps explain why the author took issue with Kubrick’s adaptation (something every fan of the film aware of this footnote must have pondered questioningly), it is also illuminating because King creates more depth behind main characters, gives more detail to the story, and adds his own brand of literary terror rather than Kubrick’s ethereal and disturbing screen vision.

One of King’s main complaints was Kubrick’s portrayal of Wendy, Jack Torrance’s seemingly vapid wife, played by Shelley Duvall. In the novel, Wendy is a much more sympathetic and frankly intelligent woman, not a terrified and one-sided Susie Homemaker paralyzed by fear. And while central to the novel’s plot and climax, Danny’s ability to “shine” is overshadowed by much of the film’s other plot elements and imagery, while telepathy is arguably the key advantage in the novel that allows Danny and Wendy to survive the insane attentions of Jack Torrance.

King would also portray the Overlook Hotel as a character in itself, evil and twisted, with a growing malice that spills out overtly into reality during the long winter months snowed in at the crest of a mountain pass in Colorado. King has to be given full credit for the origins of this idea, which is truly original, along with the growing sense of unease that the reader seems to sense when touching on the idea of isolation. While Kubrick would capture this and transform it through a lens into a film horror masterstroke, it was King’s imagination that brought it to life.

When reading the novel, it is hard not to want to inject elements of the film into the plot. While understandable considering the film’s towering status, it is almost jarring to encounter aspects of the novel’s plot that don’t conform, such as King’s anthropomorphized hedge animals which eventually come alive and wreak havoc, somewhat replaced in the film by the hedge maze where Jack Torrance meets his untimely end.

Interesting to note is at the time, Kubrick’s film opened to mixed reviews and a modest showing at the box office, despite now being considered one of the finest horror films ever made. Over the years, Kubrick nerds like myself have injected all manner of theories and commentary about the film’s imagery, scenes, and plot. Those interested in investigating the film’s real mythology as opposed to its on-screen iconography might want to open Room 237 (2012), an American documentary film that explores in excruciating detail the alleged interpretations and perceived meanings behind Kubrick’s film.

Some of the more bizarre interpretations of the film that have emerged since 1980 suggest it is either an allegory for aboriginal genocide, a loose re-telling of the mythical story of the Minotaur, Kubrick’s attempt to remind us all of the Jewish Holocaust, or most infamously that there are clues placed throughout the film that confirm he was behind faking the Apollo 11 moon landings in 1969, another urban legend conspiracy theory that has an army of followers in some of the darker corners of the Internet.

Not that I subscribe to any of these flights of fancy, based on the flimsy evidence many of these apologists use to justify their claims. While there may be some small truths to be uncovered here, I prefer to see the film as exactly what it still remains: a masterpiece of cinematic history. Few would suggest otherwise; even those that may dislike the film have to admit that Kubrick’s revolutionary cinematography and camera work elevate The Shining — not unlike almost every one of his films — into something more than just brilliance. Kubrick’s unprecedented use of the new Steadicam to capture the low-angle tracking shots of Danny’s Big Wheel journeys through the hotel are some of the most technically difficult and arresting scenes in the film, and remain visually stunning almost four decades after they graced the big screen.

What is also now legendary is the toll Kubrick took on his actors in shooting the film. Huge numbers of takes of single scenes are still held up as an example of the quintessential pretentious artist. Trouble is, when witnessing the final product it’s hard to argue with Kubrick’s slave-driving vision. Actress Shelley Duvall — who it seems wasn’t one of Kubrick’s biggest fans — apparently suffered what amounted to a nervous breakdown when the film was done shooting, and took months to recover.

On the literary side, fans of the film might be interested to know that King actually penned a sequel to his 1977 novel, Dr. Sleep (2013), which is being adapted into a film of the same name set to debut in theaters in 2020.

Adding depth to characters that might have been lacking in Kubrick’s film — especially Wendy, and to a lesser extent Danny himself — King’s The Shining stands up well under the shadow of the 1980 film, and remains an excellent example of some of King’s earlier novels which still hold greater fascination for most than his later work. Diving deeper into the terrifying past of the Overlook Hotel while taking the reader down some unexpected avenues related to plot, The Shining is worth revisiting for fans of the now-hallowed film.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Log In

Log In